- cross-posted to:

- science@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- science@lemmy.world

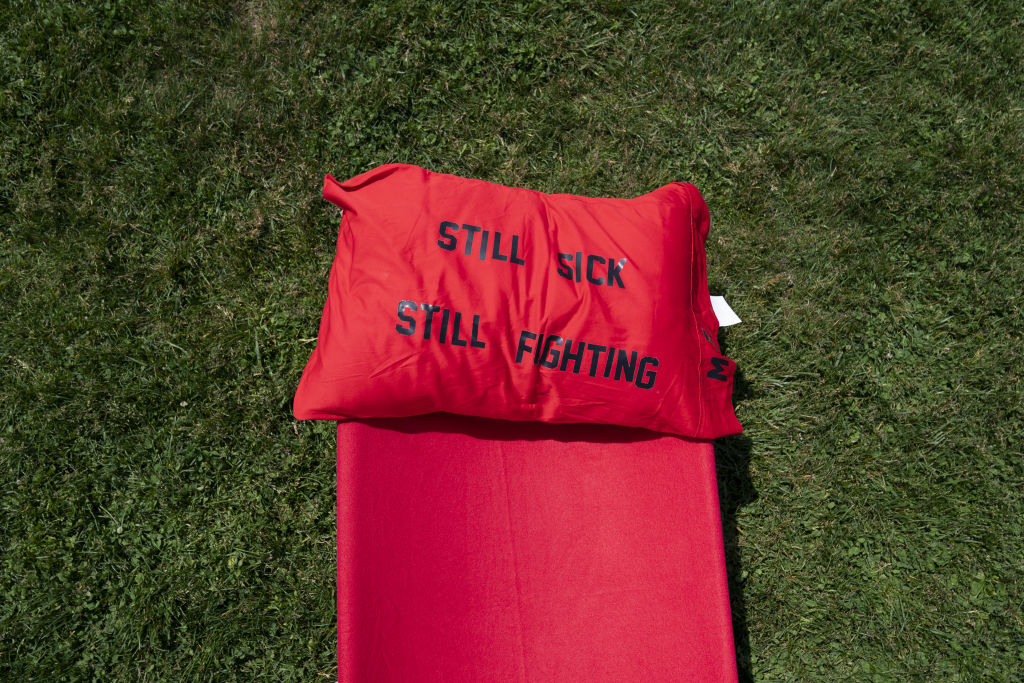

Without proven treatments, many people are still sick.

Since August 2020, David Putrino, director of rehabilitation innovation at New York’s Mount Sinai Health System, has helped treat more than 3,000 people with Long COVID. These patients, in his experience, fit into one of three groups.

A small number, no more than 10%, have stubborn symptoms that don’t get better, no matter what Putrino and his team try. A big chunk see some improvement, but remain sick. And about 15% to 20% report full recovery—an elusive benchmark that Putrino greets with cautious optimism.

“I call it ‘fully recovered for now,’” Putrino says, since lots of people’s symptoms eventually come back, sometimes if they catch COVID-19 again, which can land them back at square one.

Putrino’s outlook isn’t purposely gloomy; it’s one informed by the difficult realities of treating Long COVID, a condition with no known cure and is defined by long-lasting symptoms following a case of COVID-19. More than 200 symptoms are associated with Long COVID, commonly including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, intolerance to exercise, chronic pain, and more. Millions of people around the world have developed Long COVID, and an uncertain number have completely recovered.

“It’s really hard to tell” exactly how many people get over their symptoms entirely, says Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, a clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis who researches Long COVID. “But anecdotally, from clinical experience, the majority unfortunately don’t.”

Who gets better?

Zeroing in on the Long COVID recovery rate is a work in progress, but two recent reports from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest remission is possible.

One, based on U.S. Census Bureau data, found that roughly 6% of U.S. adults currently have Long COVID, down from about 7.5% in the summer of 2022. The other found that many people’s symptoms disappear over time. A year post-infection, people who’d had COVID-19 were roughly as likely to have lingering symptoms as people who’d had other respiratory illnesses, the researchers found. That tracks with a January 2023 study in the BMJ, which found people who develop Long COVID after mild initial illnesses can expect most symptoms to improve within a year.

Other researchers, however, have come to less optimistic conclusions. In an August study published in Nature Medicine, Al-Aly and his team found people who’d had mild COVID-19 remained at increased risk of more than 20 Long COVID symptoms—including fatigue, gastrointestinal problems, and pulmonary issues—two years later. People whose COVID-19 was severe enough that they were hospitalized were at increased risk of more than 50 health problems two years later.

The findings reflect “the arduous, protracted road to recovery" for some people who catch COVID-19, Al-Aly says—a road that many people with Long COVID are still on, according to research posted online in July as a not-yet-peer-reviewed preprint. In a group of 341 people with Long COVID, only about 8% had fully recovered after two years of follow-up, co-author Dr. Lourdes Mateu and her colleagues found.

How can multiple studies on the same topic reach such different conclusions? The way they’re designed can make a difference, Putrino says. Some Long COVID research uses data drawn from patients’ health records. In these studies, Putrino says, researchers sometimes assume symptoms have resolved if someone stops coming in for care. But there are lots of other reasons someone might stop seeing their doctor: financial constraints, frustration that treatments aren’t working, health declining to the point that leaving home becomes difficult, and so on.

“Recovery” can also be defined differently. Is it a complete resolution of symptoms, or improving enough that someone can function despite their ill health? Once researchers start splitting those hairs, Al-Aly says, they often find that someone “didn’t really recover; they adjusted to a new baseline.”

For that reason, research that takes into account patients’ own perceptions of their symptoms and recovery is important. That’s what Mateu and her team did. For two years, they tracked Long COVID patients who’d sought care at a hospital in Badalona, Spain, periodically asking about their symptoms during face-to-face visits and performing secondary diagnostic tests when necessary. With that level of scrutiny, Mateu says, the vast majority of patients did not meet their definition of recovery: the resolution of all persistent symptoms for at least three consecutive months.

Granted, the patients in Mateu’s study were a specific group. Most were infected before vaccines (which have been shown to be somewhat, though not entirely, protective against Long COVID) were available and they were all sick enough to seek care at a hospital-based Long COVID clinic. Counterintuitively, however, the people in the study who were originally sickest—those who were admitted to the ICU when they had acute COVID-19—were more likely to recover within two years than people with milder initial illnesses, Mateu says.

In some cases, Mateu says, people with severe COVID-19 are left with issues that are significant but have better prognoses than Long COVID, such as post-intensive care syndrome. People who develop Long COVID after mild illnesses, by contrast, can be more vexing. Their test results may come back pristine yet their health remains poor, making it difficult for doctors to determine what to treat and how.

NIH is studying possible treatments

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently launched clinical trials focused on potential treatments, but it’s not yet clear if any will succeed and less likely any will work for all Long COVID patients, since the condition’s symptoms can look different from person to person. The NIH will test various therapies in patients with specific symptom clusters—offering brain training for those with cognitive dysfunction, for example, and wakefulness drugs for those with sleep issues—rather than across the board.

As of now, there is no one-size-fits-all treatment for Long COVID, nor any treatment guaranteed to work at all. Each time a new patient enters their clinic, Putrino and his team start from the ground up, doing a comprehensive analysis of the individual’s health in hopes of finding a problem that may respond to drugs, supplements, nerve stimulation, or other tools.

Sometimes this approach works better than others; sometimes it doesn’t work at all. The rarity of complete recovery, Putrino says, underscores how desperately Long COVID sufferers need more extensive treatment trials, and fast.

“I feel time pressure with these patients,” Putrino says. “Every second that we’re not testing something new or trying something that’s a moonshot for these patients, they’re getting worse.”

archive link: https://archive.is/EKcy0

I suffered of long covid from alpha variant. The worst thing I have ever had because of the cronic pain and general state of inflammation.

Luckily I fully recovered. I don’t wish it to my worst enemy

This is why I still wear a mask.

This sounds severe enough to crash the global economy.

“Not enough workers” isn’t entirely due to employers being cheap and workers being more discerning, a lot of people died or were disabled.

It’s not long COVID, it’s just COVID.

It’s a serious virus. This is what the warnings and masks were for. Your immune system will fuck up your body permanently if this it colonizes the right part of your body.

How would they differentially diagnose long COVID from depression?

Long COVID includes mitochondrial and endothelial dysfunction, postural tachycardia (can’t stand up in the shower), and many other features which are not typically part of depression. Long COVID (may be better to use the term myalgic myeloencephaletis) can certainly precipitate mood disorders, but they are typically reactive, or adjustment related.

Surprising overlap between the cognitive symptoms and ADHD. I want to meet some of these people so I can summarily criticise their lack of executive function and give them self-esteem issues.

Makes me glad I caught it toward the end of February 2020 on a flight. And got vaccinated and two boosters. Might go for the trifecta just to be sure.