cross-posted from: https://beehaw.org/post/18055236

[The CCP doesn’t rewrite history, it increasingly tries to prevent it from ever being written.]

How has the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tended the gaping chasm between propaganda and reality in China’s modern history? And what do earlier historical precedents of propaganda around past atrocities bode for future propaganda on East Turkistan [or Xinjiang, as the region is also called]?

[…]

For now, the CCP’s mission to propagandize a fairyland version of East Turkistan continues apace. Along with vast amounts of content in the domestic media and sponsored content abroad, the CCP’s messaging also appears in traveling exhibitions, in “conferences,” in carefully stage-managed media and diplomatic tours of the region, and at travel shows where people are invited to “unveil the truth” about the region.

[…]

A basic metric for the scale of oppression is that Uyghurs (at barely one percent of China’s national population) comprise up to 60 percent of China’s entire prison population. Up to half of all imprisoned journalists in China are Uyghur. Uyghurs are the most likely of all inmates to die in prison. Coercive family planning policies have led to an alarming crash in the number of Uyghur births, worse even than the rates during genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda. There is evidence that forced labor programs in the Uyghur Region are expanding. Expressions of faith and cultural identity have been criminalized. But the Party would have us believe that Uyghurs are “the happiest Muslims in the world.”

[…]

History as propaganda

Party-branded history forms the essence of day-to-day Party propaganda. A famous adage states that journalism is the first rough draft of history. Conversely in China, “journalism”—communications and propaganda—is dictated and proof-read by Party historians and ideologues.

[…]

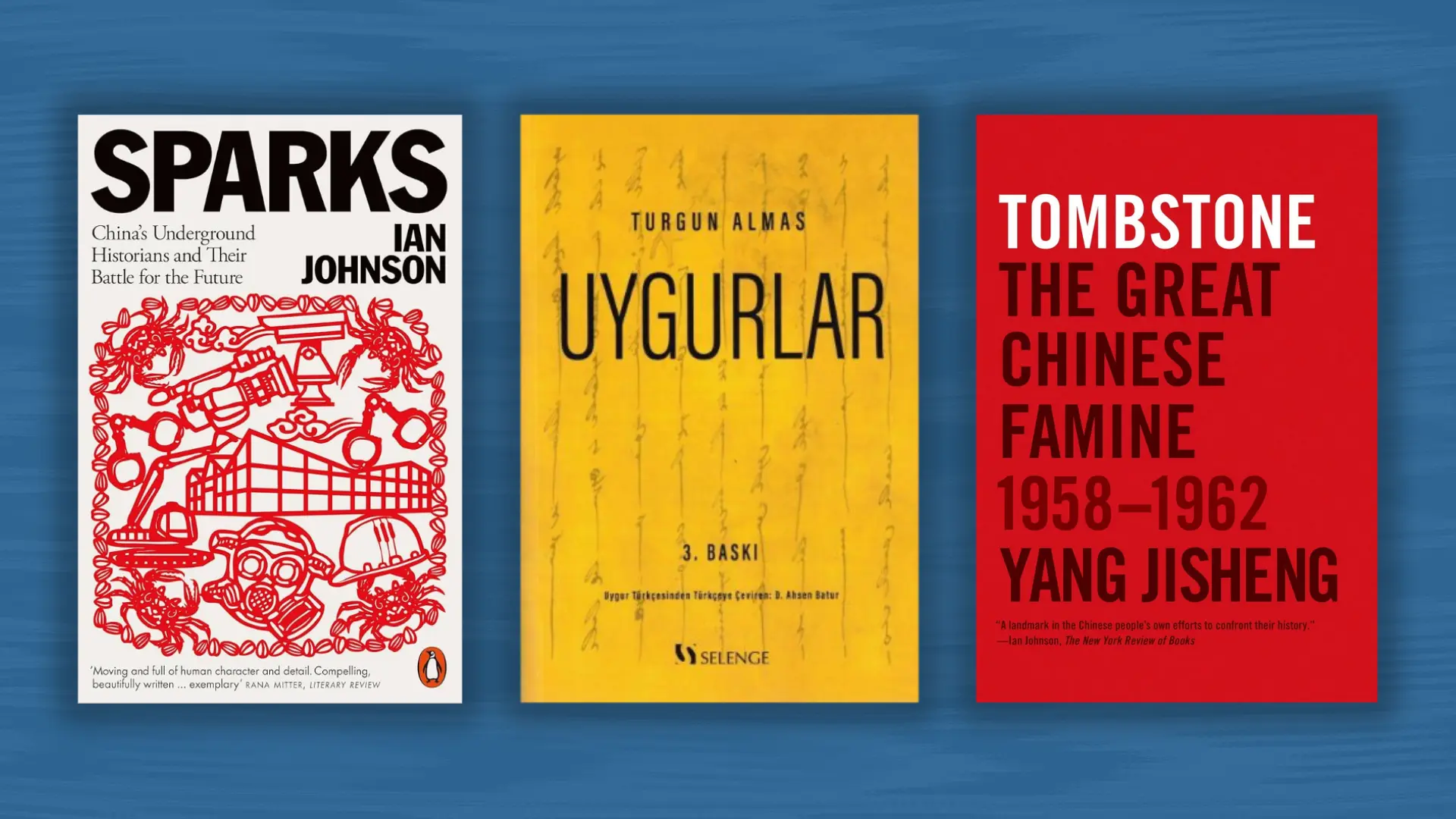

Standalone Uyghur histories are not tolerated: Uyghurlar by poet and historian Turghun Almas was quickly banned after its release in 2010. In early 2022, Sattur Sawut, a historian who drew on previous official versions of the Uyghur Region’s past was given a suspended death sentence for a history book he compiled, and three of his associates were given life sentences.

The Party-line history insists that the Uyghur Region has been part of “the Motherland” since the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), and that the Uyghur people—along with all ethnicities in the Uyghur Region—have been “members of the same big family” ever since. In other words, the Uyghur people, their land and their culture are all just scions of a greater Chinese entity. The absurd use of the metaphor of a pomegranate to describe the closeness of all ethnic people in the region is far more descriptive of Uyghurs crammed into prison cells.

And it is the CCP’s mission to wrench the Uyghur people into a state of being that affirms this telling of history as narrated by the propaganda which largely fuels human rights atrocities in the region.

[…]

The Great Chinese Famine [between 1958 and 1962] is widely regarded as the worst man-made disaster in human history. Absurdly ambitious agricultural policies were pursued to ridiculous lengths. Claims of outrageously high crop yields were championed by the Party, which then turned a willfully blind eye to the devastation their policies caused to food production. Even as people starved to death in plain sight the Party’s focus was instead on celebrating its own genius and exacting brutal recrimination against anyone who dared doubt it.

Estimates for the numbers of people who died in the famine vary between 2.6 and 55 million. One of the most rigorous studies—Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962 by former Xinhua journalist Yang Jisheng—estimates 36 million people died while another 40 million “failed to be born” due to falling birthrates.

Yang quotes Lu Baoguo, a Xinhua journalist at the time, who recounts: “In the second half of 1959, I took a long-distance bus from Xinyang to Luoshan and Gushi [in Henan Province]. Out of the window, I saw one corpse after another in the ditches. On the bus, no one dared to mention the dead.”

More than 60 years later, official accounts of the period gloss over the famine as “The Three Years of Hardship” (三年困难时期). At the time of writing, the top result from a Google search of the “gov.cn” domain using the term “The Three Years of Hardship” is a 2015 article from the “Party History Research Office of the CCP Yueyang Municipal Committee” in Hunan, which states: “In 1959, 1960, and 1961, there were three consecutive years of natural disasters coupled with the Soviet Union’s debt collection and leftist ideological interference, and the country entered a difficult period and the people lived in hardship.”2

The famine is “completely absent” from China’s history textbooks; Yang Jisheng hasn’t been permitted to leave China to accept awards for Tombstone, which hasn’t even been published in China.

Continuing to whitewash and doctor the historical record will inevitably form the foundation of the CCP’s future propaganda strategy on East Turkistan. Given the framing of the Great Chinese Famine, the closest the Party may ever come to acknowledging, for example, the astronomical rates of Uyghur imprisonment—up to one in 17 adults—will be a similarly trivializing non-confession: “The Party displayed an abundance of caution in the face of challenging domestic and international pressures, which led in some areas to an over-enthusiasm for intensive education measures.”

[…]

**The Tiananmen Massacre, June 3–4, 1989 **

The CCP Department of Propaganda’s central offices are a short tank-drive from Tiananmen Square itself—merely half a city block—and anyone there would certainly have witnessed the massacre, if they chose to.4

It’s well-known that the Department of Propaganda is adept at flooding online spaces with counter narratives and disinformation. However, the department’s other primary function is brute censorship. Every year around the anniversary of the massacre, huge volumes of material attempting to discuss or memorialize events are liable to be wiped from China’s cyberspace.

Online postings containing any one of hundreds of keywords are considered suspect. Some of the keywords are obvious: “tank man” or even just “tank,” for example. Others are a stark demonstration of the CCP’s nervousness: postings containing “candle” are suspect because some of the bereaved light candles in memory of those killed. Still other keywords are evidence of people’s ingenuity and determination to memorialize the massacre: posts containing the otherwise meaningless characters 占占点 are deleted because the characters are intended as a pictogram of tanks rolling over people.

That the Party was willing to turn the military forces of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army against unarmed Chinese citizens was a shock that still reverberates around the country 35 years on. And whereas the Party’s stance on other events may have softened over the years – some incidents are “reassessed” by Party historians and individuals once vilified are posthumously “rehabilitated” – there has been no significant deviation in the Party’s refusal to countenance any kind of public accounting for the Tiananmen Massacre.

[…]

Conclusion

The CCP employs—and will undoubtedly continue to employ—various tried and tested propaganda strategies in East Turkistan. The lesson from the Great Leap Forward is how to make the record invisible, the Cultural Revolution is a lesson in blaming others, and the Tiananmen Massacre a lesson in outright denial and the utility of the delete key. These same strategies are evident in other atrocities not covered in this article: the decimation of Tibet, the murderous campaign against Falun Gong, or the Party’s mishandling of the Covid outbreak, to name but a few.

The continuation of a people’s culture depends on the validity of their memories and experience. The challenge of maintaining the integrity of Uyghur identity is falling ever harder on the diaspora, notwithstanding the CCP’s concerted efforts to harass and silence Uyghurs abroad. This is a mission that’s well understood in the diaspora and among their supporters, but greater assistance against Beijing’s vast propaganda machine is always welcome.

Propaganda is neither a science nor an art, and for over a century there has been no true innovation in Chinese propaganda. The paradigm shifts of digital media and mass communications haven’t altered the basic impulse: dominate or destroy narratives in support of ulterior motives. As Chairman Mao put it, “Make the past serve the present.” But perhaps Churchill put it more succinctly: “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.”