I’m a little confused about what states in US are. Are they more like their own countries united in alliance, or are they districts of one country?

Starting with the title question, US States are bound by the federal constitution, which explicitly denies certain powers to the States, found mostly in Article I Section 10. The first clause even starts with foreign policy:

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

In this context, the terms “treaty, alliance, or confederation” are understood to mean some organization which would compete with the union that is the United States of America. That is to say, a US State cannot join the United Kingdom as a fifth country, for example. Whereas agreements between states – the normal meaning of “treaty” – is controlled by the third clause, which refers to such agreements as “compacts”.

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

Compacts are only allowed if the US Congress also approves. This is what allows the western US States, the federal government, and Mexico to all agree on how to (badly) divide the water of the Colorado River.

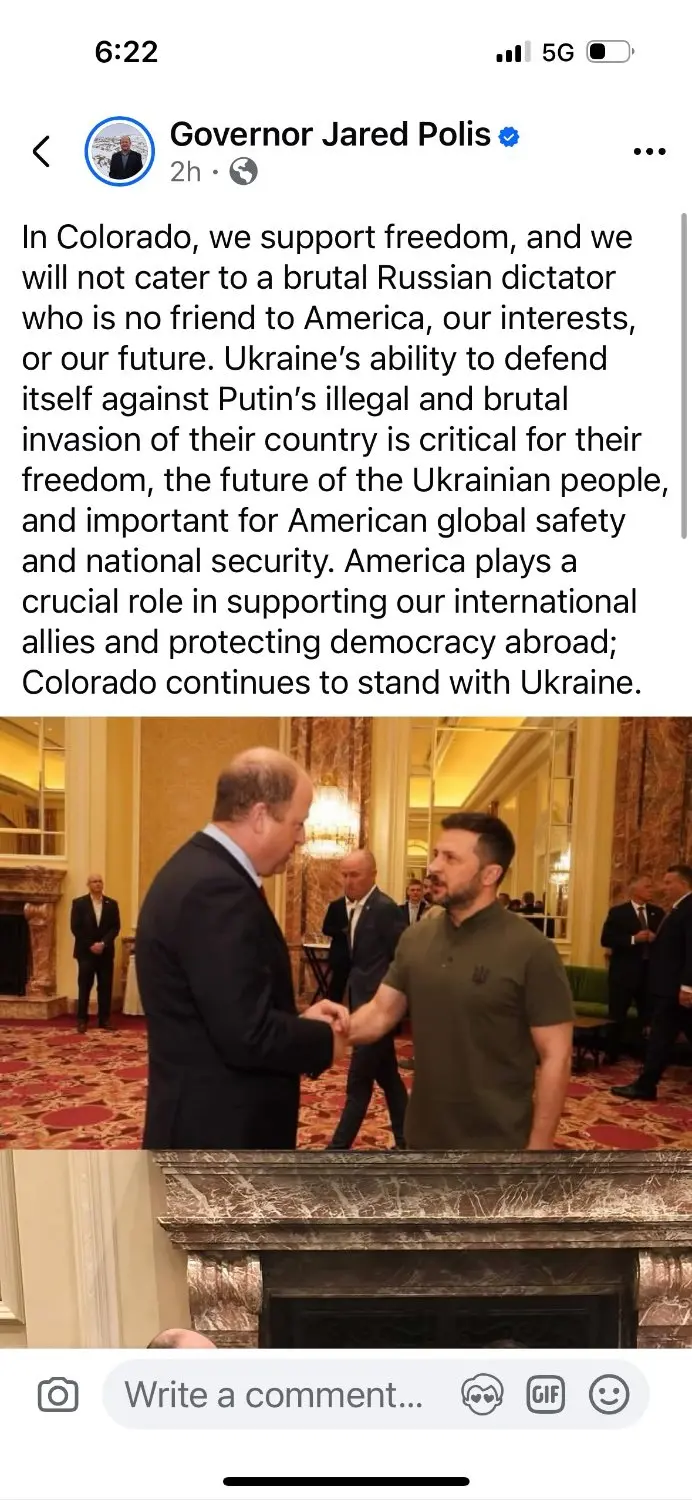

So if foreign policy is meant to include diplomatic relationships, military exercises, setting tariffs, and things like that, then no, the US States are severely constrained in doing foreign policy. The diplomatic relations part is doable, where state-elected officials can go to foreign countries to advocate for trade and tourism. But those officials must not violate the federal Logan Act, which prohibits mediating an active dispute involving the USA, since that’s the US Secretary of State’s job. For example, it would be unlawful if a US State governor tried to mediate a prisoner exchange with a country that the USA has engaged the military against.

For your other question about what US States are, the answer to the question changed significantly in the 1860s. During that decade, the federal constitution gained three amendments, with the 14th Amendment being the most significantly for the notion of statehood. That Amendment’s Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses gave life to the notion of “incorporation”, which is that the US Constitution’s limits on the federal government also applied to the several States.

Before the 1860s, US States were indeed closer to countries in a trading, monetary, and foreign policy alliance. Some US States even had official religions, since the First Amendment’s prohibition on endorsing religion only applied to the federal government. But post 1860s, it was firmly established that the federal government isn’t just some economic committee, but an actual representative body, one whose laws will trounce state laws.

The best example I can point to is how broad the federal government exercises its “interstate commerce” powers. Basically, if something has anything remotely to do with crossing a state border, the feds can write laws on that topic. That was extremely rare pre 1860s, and now it’s basically the norm. The postal service is one such activity which is explicitly and wholly a federal matter, written into the initial Constitution. But now, airspace, telecoms, and railroads are all matters which the federal government asserts its authority via the “interstate commerce” powers, and if US States were countries, they might object to the feds. But they’re not countries, so they don’t wield that power.

While I’m not a political scholar to understand the limits of their power, their leaders can certainly express their own stances.

And like most things in the US, some states have more money, power, and influence than others. It’s complicated.

legally no, but it’s not like the governor of colorado is sending ukraine weapons - they’re just words and as such do not violate the constitution. ianal, etc etc

Constitutionally, it is spelled out in Article I, Section 10, Clause 1:

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

So foreign policy is principally a federal government domain, established by cases heard by the Supreme Court. https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/artI-S10-C1-1/ALDE_00001097/

There is a somewhat gray zone where neighbors can talk to each other on the state level, e.g. Maine and Quebec. But they will find themselves restricted by what the governments one step up have decided. I think certain states also are on friendly terms with other nations, probably to deepen economic ties. But that’s more on the level of a city friendship than actual foreign policy.

There is no limit in the Constitution that prohibits individual US states from exchanging representatives with foreign countries or from expressing or sending support to them. However, there are some caveats, of course, and it’s a very nuanced area of law that has interesting implications:

- Accepting formal diplomatic representatives from another power is deemed under international law to mean recognising the independence and sovereignty of the power whose representatives you are accepting. Which essentially precludes formal diplomatic ties from consideration. This is why the US doesn’t accept diplomats from the Republic of China (a.k.a. Taiwan) and refuses official Taiwanese diplomatic and service passports, but is more than happy to accept “unofficial” representatives.

- Any representatives sent would not have the power to contract treaties as US states are not competent under US law to enter into treaties or make any other binding obligation to other countries. This is problematic because that means they can’t even do as much as rent an office space in another country without the involvement of the US federal government.

- The primary reasons that a country might consider hosting a diplomatic mission of a foreign power is so that they can (1) complain to the ambassador about that foreign power doing things that they don’t like, (2) so that the foreign power can issue passports and visas within the host country, (3) so that consular services can be provided by the foreign power to its citizens or subjects living within the host country, and (4) negotiate treaties. Since US states don’t really do anything abroad that can’t be handled or complained about through the US Department of State, and because US states don’t issue passports or visas, and because consular services to US citizens is already provided through the diplomatic missions of the United States, it is unnecessary for any country to consider hosting a US state diplomatic mission.

That’s an interesting question of Federalism, that I would argue, even the courts can’t answer. The violence of the civil war effectively answered that question: No. However, it was purely the force of violence that made that assertion. And it will be again.

The American Civil War was fought over slavery, not independence in terms of foreign policy.

While the Southern states were ultimately fighting for slavery as an institution, the question the war was trying to answer wasn’t whether states can have slavery; it’s whether states can secede. If the North was willing to accept secession (which would’ve been a massive mistake don’t get me wrong) the war wouldn’t have happened. The Southern proposition that made the North go to war was, at least to my shallow understanding, “I’ll make my own Union with blackjack and (slave) hookers”, not “I wanna keep owning slaves”.

The Southern proposition that made the North go to war was, at least to my shallow understanding, “I’ll make my own Union with blackjack and (slave) hookers”, not “I wanna keep owning slaves”.

It was “I’ll make my own Union with slaves.” Explicitly. It was written into the secession documents of every single Confederate state, clearly and in no uncertain terms, that the reason for secession was specifically to maintain and defend the institution of slavery. Period, end of.

Yeah obviously. I think I made that clear enough. I mean I put “slave” right there.

On this point it makes sense people are eager to explicitly identify slave owning as the primary driver for secession, because it’s the truth and there is still an active attempt to cover it up

The lost cause argument is something racist losers came up with after the war where they try to say it was more about states rights (and oh by the way slavery wasn’t so bad, many slaves like being slaves)

Some schools still teach this, I went to a “Northern” school and still had textbooks making this argument.

Your post seems to echo this by saying the South’s main thing was they wanted to be separate, even though that happened to include slavery, there were other reasons too. That’s not the case. When they seceded the south explicitly identified slavery as THE reason why they were doing it.

Your post seems to echo this by saying the South’s main thing was they wanted to be separate, even though that happened to include slavery, there were other reasons too.

If so let me restate/reclarify: The South mainly or exclusively because they wanted to defend and further slavery as an institution (not even own states themselves; that’s a charitable way of putting it). However, the North didn’t give a shit about the South owning slaves; they just didn’t want them to secede and why both sides came to blows. To the North the slavery thing was kinda bad but really not the point; what they wanted to do is (to oversimplify) keep the South in the Union. That’s what I was trying to say.

The American Civil war began with a Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. At the same time it was never established that you can opt out of the US, that’s generally not how countries work.

The Confederacy would not have happened if it wasn’t for fears of abolishing slavery.

Lincoln’s election provoked South Carolina’s legislature to call a state convention to consider secession. South Carolina had done more than any other state to advance the notion that a state had the right to nullify federal laws and even secede. On December 20, 1860, the convention unanimously voted to secede and adopted a secession declaration. It argued for states’ rights for slave owners but complained about states’ rights in the North in the form of resistance to the federal Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their obligations to assist in the return of fugitive slaves.

It was “states rights for me but not for thee”.

The constitution doesn’t cover if states can leave the union. Until the civil war this was an unresolved question. We now know definitively that you de facto can’t, at least not without permission of the federal government.

I’m fairly certain the next civil war will be caused by severe wealth disparity.

I wish I could just sit back and enjoy the circus from a safe distance, but the way this American dumpster fire affects the whole world just scares the hell out of me.

Yes, and a counter to the argument that the Union was inviolable versus states joining voluntarily. It might be convenient to only look at one aspect of a matter, but that only holds so long as the view agrees with the outcome you would like to happen.

The arguments around states, federalism, The Union (it wasn’t called the union for no reason): they matter. And it might be that you might find a limited interpretation around what actually happened during that time inconvenient in the future.

Why were the slave-owning states the only ones “rising concerns” around “federalism”? A curious coincidence indeed

Because they wanted to leave the union so they could carry on being slaving assholes.

Your point is obvious and dumb

States are explicitly prohibited by the Constitution from “enter[ing] into any treaty, alliance, or confederation” with foreign states, but there are plenty of cases of state and local governments joining economic partnerships and initiatives.

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.