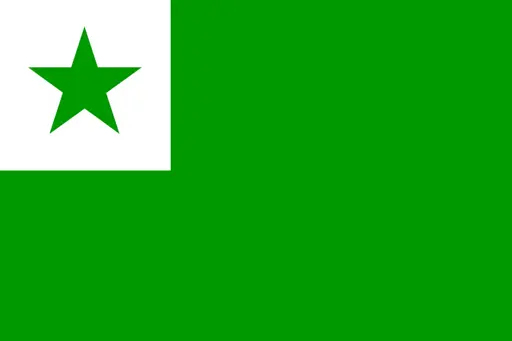

Apparently the language was popular among early 20th century socialist movements because it was of an international character and therefore not associated with any nationality and its use by international socialist organisations wouldn’t show favour to any particular country. It was banned in Nazi Germany and other fascist states because of its association with the left wing, with anti-nationalism, and because its creator was Jewish. It has mostly languished since then but still has around 2 million speakers with about 1,000 native speakers.

Esperanto, however is explicitly prescriptive. This is because early speakers believed that allowing it to evolve naturally would hinder its ability to be used as an international and universal method of communication, since past writings could end up unintelligible to future readers. For that reason, Esperanto grammar and most of its vocabulary is set in stone. The Declaration of Boulogne states that the definitive reference work for Esperanto is the Fundamento de Esperanto written by L. L. Zamenhof.

That’s all well and good, but I maintain my position both with regard to the previous commenter and – though I hadn’t meant to address it at the time – also to Esperanto. If uptake of the language is sufficient, it will devolve into dialects and further, in spite of the intentions of its inventors.

There has been some change to it over the years, such as riismo adding gender neutral pronouns, while still not going as far as complete reform like Ido. In my opinion it’s struck the right balance.