I don’t open source my code bc I don’t understand git

So, you don’t “git it”?

I’ll escort myself out.

Git push yourself out* to make the obvious joke

We are the same

git goodit’s just linked lists of commits (except when merging)

I don’t understand linked lists

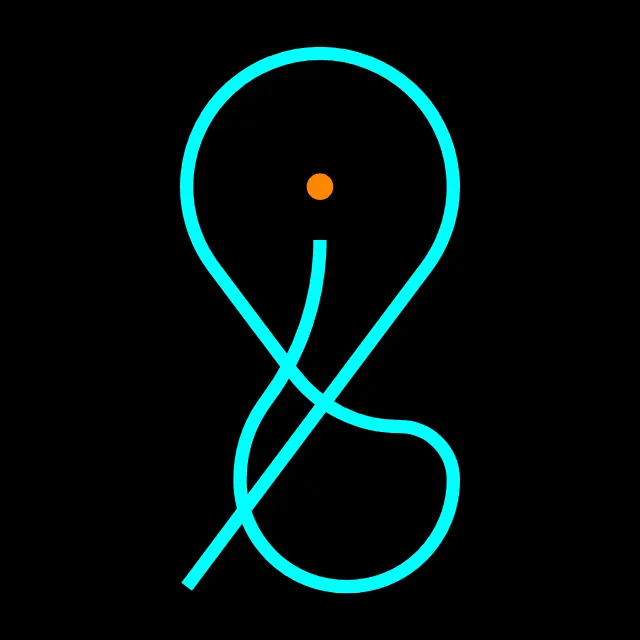

In internet terms: It’s just a soyjak holding a box with data who is pointing at another soyjak holding a box with data who is pointing at another {insert N-3 of the same soyjaks} soyjak with a box with data without an arm to point with

I don’t understand what a soyjak is.

Kourtesy of Krita

I still don’t understand Git but I like this image

each commit points to the one before. additionally a commit stores which lines in which files changed compared to the previous commit. a branch points to a particular commit.

It’s just a thingie

deleted by creator

Almost… To be precise it’s a Merkle DAG

It’s perfectly fine to just make a zip available

Branchophobic

There’s a guy out there who made a reversible NES emulator, meaning it can run games backwards and come to the correct state. He made a brilliant post on Reddit /r/programming linking his ideas for the emulator to quantum mechanics.

Then he was asked why he didn’t distribute his program in git. He said that he didn’t know git.

To me, that’s a pretty good example of the difference between computer science and software engineering.

You can open source your code just by uploading it on some kind of cloud storage and setting it as publicly available.

Jokes on you, the reason I don’t open source my code is because I never finish writing it

Commitmentphobe

Joke’s* on you

(Short for “The joke is on you”.)

Jokes on you, my apostrophe key is broken

But that’s one of the benefits of open source. Post your code and find someone else to finish it :D

Personally, I open source my code as a resume.

Is that why nobody would hire you? /s

I don’t open it because there is more comment than code…

\README.md

Nah fuck that, thats bloat.

Ah, another professional documentation writer, greetings!

Lol is it bad this is the reason I setup a self hosted gitea instead of GitHub

That’s a lot of spaghetti

Stop not open sourcing your stuff because you think it’s embarrassing. Some of the best products are made by junior devs, since they come with the fresh ideas and energy to change the status quo.

I swear I saw this posted a few weeks back

I don’t open source because the open source idea values mainly practical advantage and does not campaign for principles.

When we call software “free,” we mean that it respects the users’ essential freedoms: the freedom to run it, to study and change it, and to redistribute copies with or without changes. This is a matter of freedom, not price, so think of “free speech,” not “free beer.”

These freedoms are vitally important. They are essential, not just for the individual users’ sake, but for society as a whole because they promote social solidarity—that is, sharing and cooperation. They become even more important as our culture and life activities are increasingly digitized. In a world of digital sounds, images, and words, free software becomes increasingly essential for freedom in general.

Tens of millions of people around the world now use free software; the public schools of some regions of India and Spain now teach all students to use the free GNU/Linux operating system. Most of these users, however, have never heard of the ethical reasons for which we developed this system and built the free software community, because nowadays this system and community are more often spoken of as “open source,” attributing them to a different philosophy in which these freedoms are hardly mentioned.

Some of the supporters of open source considered the term a “marketing campaign for free software,” which would appeal to business executives by highlighting the software’s practical benefits, while not raising issues of right and wrong that they might not like to hear. Other supporters flatly rejected the free software movement’s ethical and social values. Whichever their views, when campaigning for open source, they neither cited nor advocated those values. The term “open source” quickly became associated with ideas and arguments based only on practical values, such as making or having powerful, reliable software. Most of the supporters of open source have come to it since then, and they make the same association. Most discussion of “open source” pays no attention to right and wrong, only to popularity and success; here’s a typical example. A minority of supporters of open source do nowadays say freedom is part of the issue, but they are not very visible among the many that don’t.

The two now describe almost the same category of software, but they stand for views based on fundamentally different values. For the free software movement, free software is an ethical imperative, essential respect for the users’ freedom. By contrast, the philosophy of open source considers issues in terms of how to make software “better”—in a practical sense only. It says that nonfree software is an inferior solution to the practical problem at hand.

Por que no los dos?

Why not both!