The discovery of a planet that is far too massive for its sun is calling into question what was previously understood about the formation of planets and their solar systems, according to Penn State researchers.

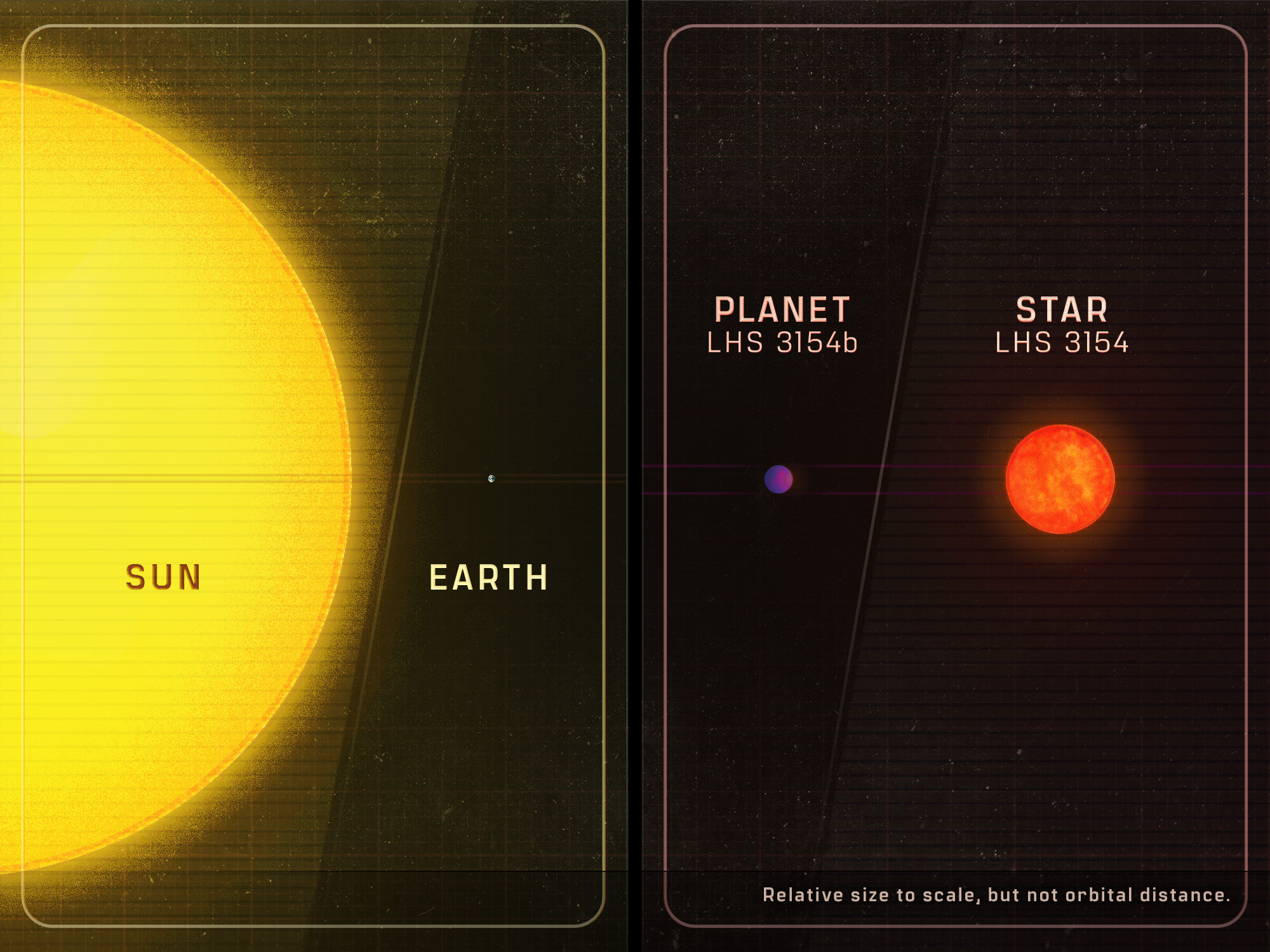

In a paper published in the journal Science, researchers report the discovery of a planet more than 13 times as massive as Earth orbiting the “ultracool” star LHS 3154, which itself is nine times less massive than the sun. The mass ratio of the newly found planet with its host star is more than 100 times higher than that of Earth and the sun.

The finding reveals the most massive known planet in a close orbit around an ultracool dwarf star, the least massive and coldest stars in the universe. The discovery goes against what current theories would predict for planet formation around small stars and marks the first time a planet with such high mass has been spotted orbiting such a low-mass star.

The close orbit makes that less likely, due to the way orbits work. Even if the planet was moving very slowly when it encountered the star, it accelerates as it gets closer and would end up with an elliptical orbit with a farthest point at about the same distance away as when the star first became a dominant force on it. If it were our system, the planet would spend most of its time in the Ort Cloud and occasionally it might venture into the area the gas giants live in or maybe even the inner solar system. It wouldn’t necessarily be on the same plane as the other planets, too.

In order to find a close orbit and stay in it, it would have to kick other planets out, giving its momentum away when it was close (which makes it rarer than just a capture, especially considering it might not even be on the same plane as other planets in orbit). Or some other event would need to perturb the orbit just right.

But unlikely doesn’t mean impossible.