- cross-posted to:

- workreform@lemmy.world

- ghazi@lemmy.blahaj.zone

- cross-posted to:

- workreform@lemmy.world

- ghazi@lemmy.blahaj.zone

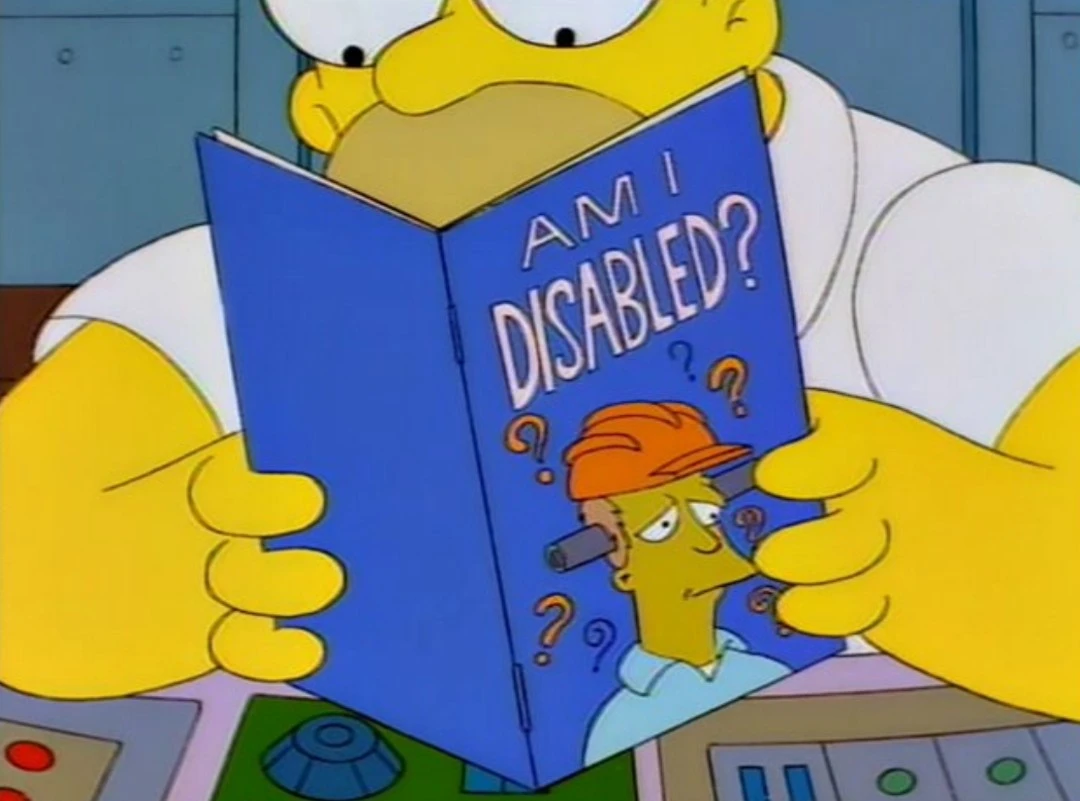

The answer: worker rights and employment protections.

Employers hate these few small tricks/strong government and or organizational regulations.

one of the key provisions of the country’s employment law, specifically on the “doctrine of abusive dismissal,” is that “employers can’t just shed employees.” They can only do so, says Matanle, “when the employer can prove that the organization would go bust.”

Should a Japanese company be found to break the law by, say, reducing its workforce to cynically juice the numbers of a quarterly report, dismissed employees are liable to be reinstated. “You can imagine the relationship problems,” says Matanle, “of staff who have won a court case against the organization for aggressive dismissal.”

Sure would like some of those employment rights here in America right about now.

Obviously Japan has got their employment rights policies more correct than the US but there are some trade-offs to having policies like this. The main one would be that employers are less likely to “give a chance” to a candidate who has limited experience entering an industry if it is difficult to fire them when if it doesn’t work out.

Economists have pointed to this being a factor in high youth unemployment rates in countries like France and Spain.

Indeed. Every job requires experience, but you have no chance of earning that experience unless you already have it, so no there’s way of getting that job.

This is the best summary I could come up with:

Typically, layoff season arrives around Christmas: a flurry of pink slips, empty desks, the anxieties of the newly unemployed, all so companies can cut costs and fatten up bottom lines just before the calendar year ends.

Matanle outlines a historic picture not of innate employment rights but one in which Japanese courts, at key moments, such as 1975’s Nihon Shokuen Seizō case, ruled in favor of workers and unions.

Should a Japanese company be found to break the law by, say, reducing its workforce to cynically juice the numbers of a quarterly report, dismissed employees are liable to be reinstated.

Finally, there are haken, dispatch workers or “hired guns,” says Colin Williamson, lead tech artist at 17-Bit who has worked in Japan for 15 years including a stint at Square Enix in the aughts.

Serkan Toto, a veteran analyst of the Japanese games industry based in Tokyo, points to the country’s long-term shrinking population (down 837,000 in 2024) as an additional factor that could theoretically benefit workers by pushing up demand for their services.

The actions of Embracer’s C-suite and those at video game companies couldn’t stand in sharper relief to the famous words of Nintendo’s Iwata who, just over a decade ago, said, “I sincerely doubt employees who fear that they may be laid off will be able to develop software titles that could impress people around the world.” These are the words Miyazaki was referencing when he spoke about avoiding layoffs at FromSoftware: it is not just the angst, nervousness, and worries of an endemic layoff culture that affects work but also the practicalities of securing alternative employment, drawing focus away from the task at hand.

The original article contains 1,702 words, the summary contains 278 words. Saved 84%. I’m a bot and I’m open source!

The US tech industry isn’t actually cutting jobs, they are doing salary rebalancing and trying to push out WFH at the same time. Tech salaries in Japan (and Asia in general) never got out of hand like they did in the US during COVID.