- cross-posted to:

- comicbooks@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- comicbooks@lemmy.world

Some debates among superhero fans will never be resolved. Superman vs. Batman. Iron Man vs. Captain America. DC vs. Marvel. But if there’s one thing everyone seems to agree on, it’s that 1986 is the most important year in comic book history. The argument why is simple — that one year saw the release of several groundbreaking comics:

- Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, an epic story about an elderly Batman who comes out of retirement to save Gotham City in the face of American decline.

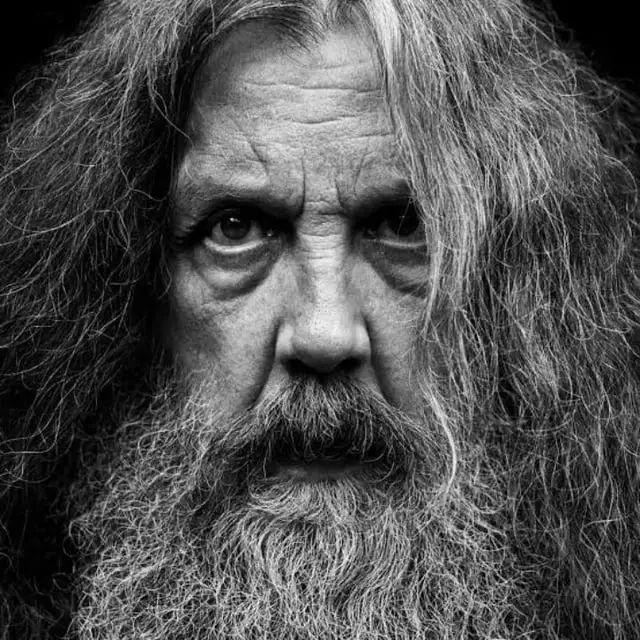

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen, a meticulous deconstruction of the entire superhero genre that’s also just a damn-good comic.

- Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which retold the story of the Holocaust to terrific effect in comic book form.

…

But before Gibbons and Moore could deconstruct the entire superhero genre with Watchmen and change comics forever, they had to take on the most iconic superhero of them all.

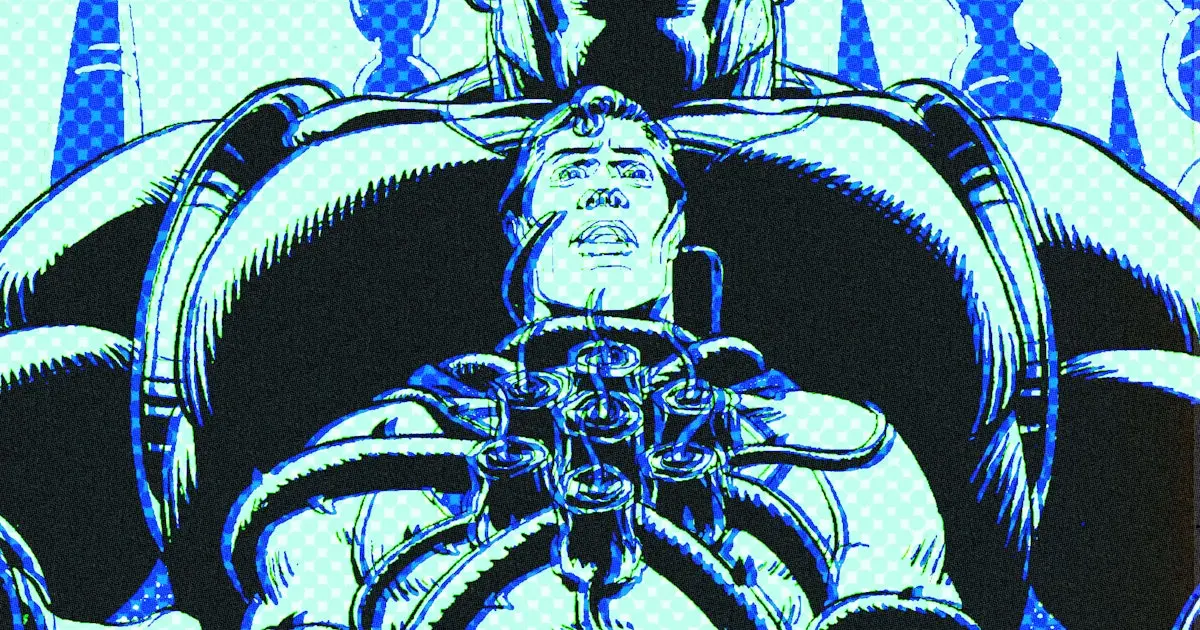

Released in 1985, “For the Man Who Has Everything,” is a Superman story unlike anything that came before (or after). The comic traps its hero in an alternate universe where his home planet of Krypton was never destroyed and he never left for Earth. Instead, Kal-El (aka Superman) lives a simple, fulfilling life with his wife and children, but what should feel like a utopia quickly gives way to social upheaval and violence. Moore and Gibbons imagine a version of Krypton that reflects the worst of our own society: crime, drugs, riots, xenophobia, police brutality, and a Ku Klux Klan-esque rally all quickly overwhelm Superman’s vision of a perfect life.

In just 40 pages — while also fitting in a B-plot where Wonder Woman, Batman, and Robin fight an evil alien — “For the Man Who Has Everything” tells a powerful allegorical story that still resonates.

…

“For the Man Who Has Everything” paved the way for the sort of social and political commentary we now take for granted in mainstream superhero stories. Without this one comic (and the deluge of instant classics that followed a year later) today’s superheroes would be a lot less interesting. But to understand how this shift was even possible, we have to go back to a time when a generation that grew up on comic books finally got a chance to make some of their own.